Post-Traumatic Urbanism

Cities like Mumbai and Beirut have developed in unstable uncertainty and in many ways are resilient survivors. They have adapted with 'redundant networks' and 'diversity and distribution' rather than 'centralized efficiency' which makes them flexible in the face of shocks to infrastructure (Lahoud, 2010).

Mumbai as a city has undergone several traumatic events in the past few years. Those in my direct memory and experience are the 26/11 attacks and the painfully recent 2011 bombings. Earlier I argued that despite these tragic events the city in essence remained the same. How does a city survive these traumatic events whether they are natural flash floods or terror attacks, and in what way does it change? Today people try to understand how cities survive and evolve through math and science. As a philosophy urbanism states that cities are vitally important to the progress of humanity. In his talk The Surprising Math of Cities and Corporations, West argues that cities are both the solution and the problem, underlining their bipolarity.

And the tsunami of problems that we feel we're facing in terms of sustainability questions, are actually a reflection of the exponential increase in urbanization across the planet... However, cities,despite having this negative aspect to them, are also the solution. Because cities are the vacuum cleaners and the magnets that have sucked up creative people, creating ideas, innovation, wealth and so on. So we have this kind of dual nature. (Geoffrey West, 2011)

West explains why cities are so successful when he says 'You could drop an atom bomb on a city, and 30 years later it's surviving. Very few cities fail.' Mumbai as a city has survived several traumatic events over the past two hundred years, though nothing on such a catastrophic level. It is an ancient place that has been ruled by a succession of invaders. There is even evidence that suggest that the islands have been colonized by humans since the Stone Age. Each event in this recorded and unrecorded past have changed the landscape and its people, but I am most interested in its recent traumas.

So cities are extremely successful, bipolar creatures. But how do traumas affect them? Philosopher and critical theorist Andrew Benjamin says that 'trauma involves a more complex sense of place.' He proposes that the city contains forgotten and repressed settings that are beyond memory but always present, creating an 'estrangement' and sense of the 'unaccustomed' when such events return.

The term 'post-traumatic' refers to the evidence of the aftermath - the remains of an event that are missing. The spaces around this blind spot record the impression of the event like a scar. (Lahoud, 2010. p.19).

Cities like Mumbai and Beirut have developed in unstable uncertainty and in many ways are resilient survivors. They have adapted with 'redundant networks' and 'diversity and distribution' rather than 'centralized efficiency' which makes them flexible in the face of shocks to infrastructure (Lahoud, 2010). When it comes to events like the most recent bomb attack in 2011, the city picked up the pieces and went on the next day as if nothing had happened. Local trains continued to run. The event was given its significant narrative by the media and the places that were bombed were cleared up. Memories and the gaps created by such violence will always remain an intrinsic part of the city's architecture. But it is Mumbai's impenetrable resilience in the face of such catastrophes that fascinates me. Events such as 9/11 in a first world country completely derailed the city, but in Mumbai it was in many ways business as usual. But forgetting like we do in Mumbai does not erase the hurt.

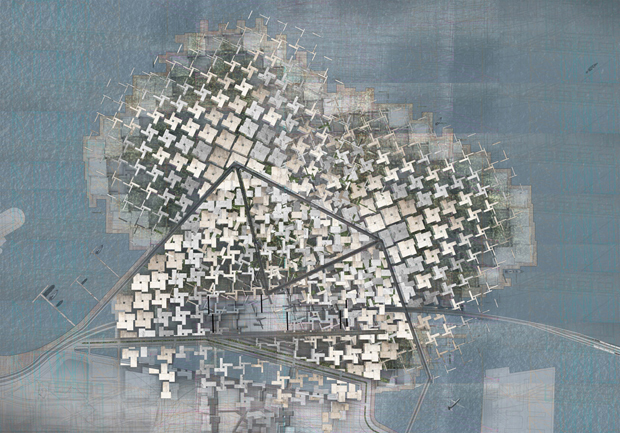

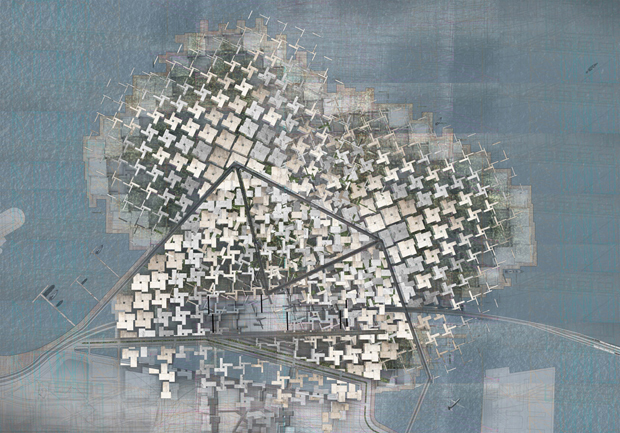

The Diversity Machine and Resilient Network, 2009. Social Transformation Studio. Martin abbot, Georgia Abbot, Clare Johnston, Joshua Lynch and Alexandra Wright.

The Diversity Machine and Resilient Network, 2009. Social Transformation Studio. Martin abbot, Georgia Abbot, Clare Johnston, Joshua Lynch and Alexandra Wright.

Anthony Burke says that the reason cities are so difficult to predict is that they are very complex systems 'growing at the edge of chaos.' Even small events can lead to avalanche-like conditions because both natural and human-made catastrophes display a self-organizing criticality or the:

...tendency of large systems with many components to evolve into a poised, `critical' state, way out of balance, where minor disturbances may lead to events, called avalanches, of all sizes. Most of the changes take place through catastrophic events rather than by following a smooth gradual path. The evolution to this very delicate state occurs without design from any outside agent. The state is established solely because of the dynamical interactions among individual elements of the system: the critical state is self-organized. Self-organized criticality is so far the only known general mechanism to generate complexity. (Per Bak, 1997, p.1).

The idea that a city is on the verge of chaos is not far from many narratives in western popular culture. The accepted line is that just one push is enough to bring the whole system crumbling down. However the theory above is not as simple as that, these systems are large and therefore extremely difficult to destroy completely. Its heartening to see that even human cities are in the end, part of nature, and follow patterns similar to natural phenomenon such as weather.

Although there are no definitive answers to what post-traumatic urbanism is the term itself raises critical questions and discussion. An often quoted statistic today is that the urban world is larger than the rural world, which underlines the importance of trying to understand urban trauma and its effect on the city and its people. In my journey to capture the essence of Mumbai, to explore unexpressed feelings of conflict created by repressed events and resolve my own perceptions and experience; it is this complexity which is central to understanding my art.

Reference: Benjamin, A. (2010). Trauma within the Walls: Notes towards a philosophy of the city. Architectural Design. Vol. 80. No.5. pp.24-31. Burke, A. (2010). The Urban Complex: Scalar probabilities and Urban Computation. Architectural Design. Vol. 80. No.5. pp.87-91. Lahoud, A. (2010). Post Traumatic Urbanism. Architectural Design. Vol. 80. No.5. pp.14-23. Per Bak. (1996). How Nature Works: The Science of Self-Organised Criticality. Copernicus Press: New York. West, G. (2011). The Surprising Math of Cities and Corporations. [online]. Available from http://www.ted.com/talks/geoffrey_west_the_surprising_math_of_cities_and_corporations.html [Accessed 2nd Aug. 2011].

Collaboration: The Third Hand

Through collaboration the singular voice of the artist is muted or dispersed, it is a break away from a singular artistic identity. The author introduces the idea of a 'third hand,' or ghost artist which is an elusive other or combined identity created in collaborative works. This third independent existence is in itself 'uncanny' because such a constructed ghost identity 'blurs the distinction between the real and phantasmic.'

[A summary of ideas from the book The Third Hand - Collaboration in Art from Conceptualism to Postmodernism].

The book focusses on a period of western art history during the 1960's and 1970's which the author identifies as the beginnings of artist collaboration, a conscious movement away from individual lone artists making work in a conventional studio. He describes and classifies three kinds of collaborative artist teams. What most interested me in the discussion of the meanings and motivations behind various types of collaboration, was the issue of identity.

Through collaboration the voice of the artist is muted or dispersed, it is a break away from a singular artistic identity. The author introduces the idea of a 'third hand,' or ghost artist which is an elusive other or combined identity created in collaborative works. This third independent existence is in itself 'uncanny' because such a constructed ghost identity 'blurs the distinction between the real and phantasmic.'

The author's discussion of the uncanny helped me better understand my previous collaborative project Tobari No Akari 2. Using dolls, dream-like doubles and shadow doubles the images we created are surreal and uncomfortable, bringing forth memories from childhood but in a disconcerting way. We could also say that creating ghost doubles in the installation references the joint artistic will of the collaboration and work itself.

The video shown below is an attempt to document the collaborative process where we arranged and re-arranged the installation over several hours. It highlights the importance of collaboration as a method of creating more avenues of future work; as well as the potential for it to be a work of art in terms of performance.

The author also talks about artists that use collaboration as a means to escape personal limits and language, to travel beyond conventional authorship and representations of identity, or a 'relativisation and reformation of self.' I felt this was especially relevant to the motivation behind my collaborative projects; however I hesitate to deconstruct or over-explain the experience for fear of losing sense of its meaning and to some extent, its mystery.

Site-Specific Art

In his book Eyes of the Skin, Pallasmaa talks at great length about the beauty of human perception and how the senses interact with each other to form experience. He emphasizes the importance of a sense experience as a whole. He says there is a bias to the eye in the architectural practice because people are focussed on how a building looks rather than how a body can move within it or how it feels. When it comes to the perception of places he discusses the importance of emotion, memory, imagination and fantasy.

During my research into place-making in phase two I briefly discussed the rigidity of a panoramic city view and my attempts to break it by framing unfamiliar cityscapes, using shadows and through collaboration. The book is relevant to my studies because it discusses creating place, the transitive nature of site, framing and virtual and 'real' spaces. The author describes monuments as loci's of power and authority (Kaye, 2000) in his chapter on Performing the City. This underlines the rigidity of the panorama since monuments are an iconic part of them. A relevant example is Mumbai's famous Nariman Point which is named after a historical Congress party leader and contains Indian and international financial institutions and government buildings such as CBI, RBI, Mittals, Birla's, JP Morgan, Merrill Lynch, Vidhan Sabha etc.

Monumentality […] always embodies and imposes a clearly intelligible message. It says what it wishes to say - yet it hides a good deal more: being political, military and ultimately fascist in character" (Lefebvre, 1991 cited in Kaye, 2000, p. 34).

He also discusses the relation between the body and the city or built environment and the body and the space, which in this case is the installation space in artist Wodiczko's work. A completely artificial and constructed installation is also a built environment. People interact with the architecture of the city, and similarly the audience interacts with the architecture of installation. The artist says that 'Our position in society is structured through bodily experience with architecture' (Wodiczko, 1992 cited in Kaye, 2000, p. 38).

In the installation test below, the audience directly affects an abstracted view of the city. In this constructed space people can directly change and affect an image of the architecture, making it fluid and interchangeable.

The author says 'where the site functions as a text perpetually in the process of being written and being read, then the site-specific work's very attempt to establish its place will be subject to the process of slippage, deferral and indeterminacy in which its signs are constituted' (Kaye, 2000, p. 183).

Further reading lead me to Merleau-Ponty's theories of phenomenology and perception where he discusses the essence of perception and experience. He says that we cannot separate our minds and bodies from our perception of the world, or in other words that we are 'condemned to meaning' (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. xxii). In his book the Phenomenology of Perception he discusses the relationship between reflective and unreflective experience, psychological and physiological aspects of perception, and consciousness as a process that includes feeling and reasoning.

We must not, therefore, wonder whether we really perceive a world, we must instead say: the world is what we perceive. (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, xviii).

In his book Eyes of the Skin, Pallasmaa talks at great length about the beauty of human perception and how the senses interact with each other to form experience. He emphasizes the importance of a sense experience as a whole. He says there is a bias to the eye in the architectural practice because people are focussed on how a building looks rather than how a body can move within it or how it feels. When it comes to the perception of places he discusses the importance of emotion, memory, imagination and fantasy:

We have an innate capacity for remembering and imagining places. Perception, memory and imagination are in constant interaction; the domain of presence fuses into images of memory and fantasy. We keep constructing an immense city of evocation and remembrance, and all the cities we have visited are precincts in this metropolis of the mind. (Pallasmaa, 2005, p.67).

In my attempts to create a feeling of conflict within the city, a subtle realization of the bipolarity within Mumbai, the result was a space that could not be expressed as a still image. Not could it be expressed by only video. By adding a third dimension of time and motion, where the audience themselves make the image change and break the city is read as something in constant flux.

I know myself only in my inherence in time and in the world, that is, I know myself only in ambiguity. (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p.402).

Reference: Kaye, N. 2000. Site-Specific Art: Performance, Place and Documentation. Routledge: London Merleau-Ponty. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception. Routledge: London. Pallasmaa, J. (2005). Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. John Wiley & Sons: UK. View Wodiczko's Bio & Work in detail.

A Short History of the Shadow

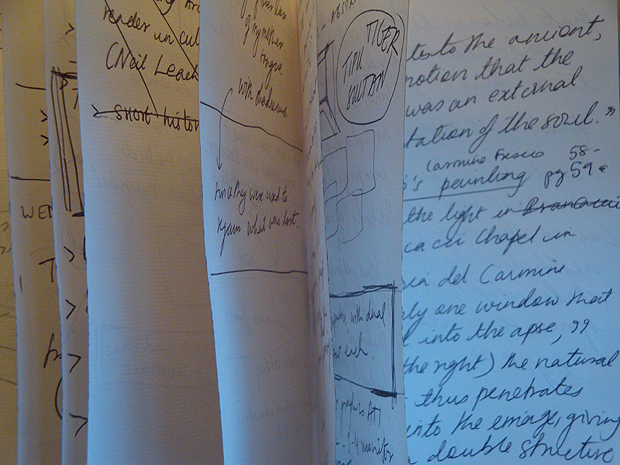

In this book the author explains the history and meaning behind the shadow in western art. Beginning with the shadow's role in the origin of painting, Victor I.Stoichita covers its symbolic significance across history, from Renaissance painters to Picasso, Warhol and even Piaget's child psychology. Over time he explains how the shadow came to represent negativity, or how the shadow was demonized. The excerpt below is from the first chapter which deals with the earliest representations of the shadow, infused with magical properties, and at times representing the soul.

"...As Maspero reminds us in his classic study, the shadow was how the Egyptians first visualized the soul (ka). In this case it was a 'clear shadow, a colored projection, but aerial to the individual, reproducing every one of his features'. And the black shadow (khaibit), having been regarded in even earlier times as the very soul of man, was subsequently considered to be his double." [pg 19]

An interesting point brought up was the difference between a shadow in sunlight and a shadow at night. He says "..a shadow in sunlight denotes a moment in time and no more than that, but a nocturnal shadow is removed from the natural order of time, it halts the flow of progress." This is relevant because day versus night is a recurring theme in my work since October last year. It also reminded me of the work Tobari no Akari, which to me signified stillness and a frozen moment in time due to the use of nocturnal shadows.

The author's comparison of specular representations with the shadow is also relevant to my work. For example mirrors and reflections in water represent a double (mimesis or likeness) of the real object or person, whereas the shadow can represent the other: "The frontal relationship with the mirror is a relationship with the same, just as the relationship with the profile was a relationship with the other." Giorgio Vasari, The Origin of Painting, 1573, fresco Casa Vasari, Florence.[pg.41]

The book lead me to question the role and significance of the shadow in my work. I've used the shadow in my first installation as a negative symbol to represent the darker hidden city. Whereas in collaborative work such as Tobari no Akari and concept work Beedi Leaf the significance is contextual and at times open to interpretation. Similarly the author underlines the changing meaning of the shadow, "...we could say that to Lippi the shadow as a symbol, is an interminably interpretable symbol." [pg.82]

Although my study of the shadow as a signifier will continue, I cannot find much information about the history of the shadow in Indian or Eastern Art. Besides brief excerpts on shadow puppetry I've discovered only limited information on the significance behind this ancient tradition.

Update: More on the significance of the shadow in the east here.

Reference

Stoichita,V (1997). A Short History of the Shadow. London: Reaktion Books Ltd.

Turner,C and Stoichita,V (2007). A Short History of the Shadow: Interview with Victor I. Stoichita. Cabinet Magazine Issue 24 [online] Available from http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/24/stoichita.php [Accessed 26th April 2011].

Warner, M (2007). Darkness Visible Cabinet Magazine Issue 24. [online] Available from http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/24/Warner.php [Accessed 26th April 2011]